By Seth Ferranti, Contributor

Huffington Post

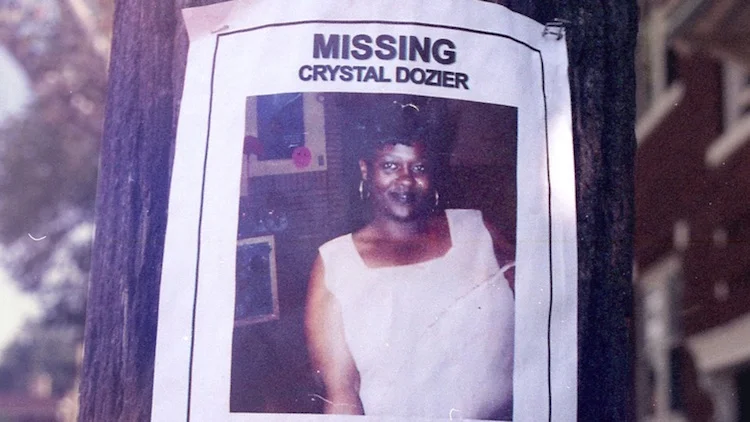

For two years numerous women went missing in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood. But nobody really cared because these woman were junkies and prostitutes and crack heads, marginalized women in poverty-stricken areas where people tended to keep to themselves. Finally a reported rape leads police to a house of horrors. A serial killer in the ghetto, operating virtually unopposed. Blending into the crime-ridden and drug-inflicted area and perpetrating ghastly murders in the confines of his own abode. A spooky looking killing den that has since been torn down.

Filmmaker Laura Paglin has constructed a riveting tale of the killer, Anthony Sowell, told through the eyes of the victims. The survivors who just happened to get away from Sowell before being brutally killed and buried in the basement. Unseen premieres at DOC NYC on November 11. I sat down for a chat with Laura before the premiere to find out why she made this film about a serial killer that isn’t really about him at all. It’s a scathing indictment on how society treats these marginalized women who suffer from addiction and poverty.

On the surface this is about a serial killer, but really it’s a story about addiction. Explain. Actually I’d go a step further and say it’s really a film about women who are stigmatized, despised, ignored literally “unseen” because of their addiction and possibly because of their class, race and gender. Being lured into a serial killer’s house, having even the smell of one’s decomposing body go unnoticed for two years means these women paid the ultimate price not only for their addiction but also society’s indifference towards them.

The film had a very steady vibe all the way through, was this intentional or how did you establish the rhythm of the film? I had an early, clunky rough cut of the film where the story sort of progressed as you’d expect it in chronological order. I included all kinds of things that I thought were interesting and far more details about the individual stories. But this ultimately bogged the film down. One thing my editor, Nels Bangerter (“Let the Fire Burn” “Camera Person”), insisted on was making sure the audience wasn’t ahead of the story. So we arranged the scenes in a kind of non chronological order where you’d get just enough of the idea before being hit with something new. While I wanted the theme of the film to be about the women and society’s attitude towards them, we also had to be careful that the film not feel like a documentary about crack addiction. Ultimately it became a careful balancing act of telling the story of the women and threading the story of the Sowell murders throughout in order to maintain tension.

Where is Anthony Sowell now and when will they kill him? Do you think he knows about your film? Sowell is in on death row in Ohio. Because of his age, he will never be executed. He will likely appeal and appeal until he dies in jail. I have no idea what kind of access he has to the outside world so can’t even speculate if he knows anything about the film.

How long did it take you to find the survivors and convince them to tell their stories and why did you decide to focus from this angle? While the discovery of the crimes occurred in late 2009, it took a long time for me to gain access to the survivors. At that point, I didn’t even know who all of the survivors were. The trial was delayed until the summer of 2011 and a gag order placed on everyone testifying. I made contact with some of the survivors when they testified in court but others were harder to track down. By 2013, I had interviewed most of the subjects I needed for the film but lack of funding and other complications delayed the film’s finish.

I wanted to tell a human story and have never been interested in making a “inside the life of a serial killer” type of piece. I was also fascinated by the once thriving, closely knit neighborhood of Mount Pleasant where the crime occurred and wanted to treat it as character that sort of paralleled the lives of the women. Before starting the film, I had a picture in my head of what a I thought a crack addict was and was really surprised when I met survivors Vanessa and Latundra in person for the first time. Both seemed like women I’d want to sit down and have coffee with. I wanted the viewer of the film to relate to these women and think “wow, that could actually be me”.

What does society’s treatment of these women- the drug addicted, the poor, the seemingly expendable- show? The killer, Anthony Sowell, took advantage of the attitudes already present, the idea of treating women who were poor, black and addicted as non-people or as “crack heads”. I think there’s quite a contrast with the current heroin epidemic. These new addicts (many white and middle or upper class) are being treated with more compassion. Even conservative lawmakers are now imploring us to treat heroin addicts as people with an illness that needs to be treated, not as criminals who need to be locked up. Sadly there wasn’t this same compassion for Sowell’s victims and the generations of mostly African American families destroyed by the crack epidemic.

You minimized the main focus of the film, Anthony Sowell, to tell the story through the eyes of the survivors and locals. This shows the impact on the community as a whole. Explain. In a lot of tabloid type format shows that feature serial killers or any killer, the victims are merely there to facilitate the story of the killer. In UNSEEN it’s kind of the opposite. I’m really telling the story of addicted women and the community they lived in, using the serial killer as a vehicle. My ultimate goal was to humanize these women who became so dehumanized because of what they went through and I think the film achieves this. I do feel that by giving these women a voice, I am empowering them. I can’t speak for them but I think for some, the experience was cathartic and possibly a step in their healing process and moving forward with their lives.